This week, NASA celebrated its 55th anniversary. On 29 July 1958, President Eisenhower signed into law the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which authorized the creation of a new civilian agency named the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The act formalized the United States' predominantly military space operations and also marked the end of the 42-year old National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which previously provided oversight on the existing disparate pre-spaceflight activities underway across the country. NASA's foundation came at a time when tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were significantly ramping up. The launch of Sputnik by the Soviets in October 1957 has a clear subtext beneath the scientific overtones—the Soviets controlled the high ground, and could overfly the United States from orbit with total impunity. Nuclear war was considered a real possibility, and its likelihood would only increase over the next five years. Although it was a civilian agency, NASA's formation was a highly political action—as was its goal. Thanks to conversations between President Kennedy and deputy director Hugh Dryden, the agency was targeted almost from its inception at landing Americans on the moon. The accomplishment would be mostly symbolic—at least at first—but it had two hidden bonuses. First, the estimated cost of tens of billions of tax dollars pumped into private industry across the country would assure its popularity with the US people. More importantly, it was also designed to force the Soviets to spend their own money on a matching effort, the existence of which the Soviets denied until just before the USSR's dissolution. Running out of the gate: Mercury and Gemini In the early years, all roads led to Apollo...but those roads were utterly unmapped. In order to land on the moon, NASA engineers and managers designed a decade-long set of tests to figure out how to create the materials, procedures, and technology necessary to land on the moon. The first step was proving humans could survive and operate in space; to that end, Project Mercury started with seven highly trained pilots and transformed them into the United States' first astronauts. Shepard, Grissom, Cooper, Schirra, Slayton, Glenn, and Carpenter—many of the names, even today, still have a celebrity ring to them. The seven Mercury astronauts were treated as heroes and gods by the media of the day, and even though Project Mercury didn't put a human in space before the Soviets managed it, it blazed its own parallel trail as fast as their rockets could taken them. After Mercury came Project Gemini, with bigger spacecraft and more ambitious missions. Gemini's goal was to prove that humans could survive outside of their spacecraft (something which the Soviets again did first), and also to allow NASA to figure out how rendezvous in orbit worked—knowledge absolutely critical to landing on the moon. Gemini and Mercury were stunning successes. We were on our way. NASA Alan B. Shepard takes flight in Freedom 7 on 5 May, 1961. Shepard's 15-minute suborbital flight marks the first manned Mercury mission and first time an American entered space. Keenly aware of the political pressure to have a successful launch, Shepard is (apocryphally) credited with coining "Shepard's Prayer" shortly before the launch.  NASA Alan B. Shepard takes flight in Freedom 7 on 5 May, 1961. Shepard's 15-minute suborbital flight marks the first manned Mercury mission and first time an American entered space. Keenly aware of the political pressure to have a successful launch, Shepard is (apocryphally) credited with coining "Shepard's Prayer" shortly before the launch.  NASA The second Mercury flight, Gus Grissom in Liberty Bell 7, did not end as successfully as Shepard's. The spacecraft's hatch blew out shortly after splashdown, almost drowning Grissom and causing the capsule to be lost beneath the ocean's surface. Grissom is pictured here on the deck of the recovery ship, the USS Randolph, with no small amount of emotion visible on his face. Later investigation proved conclusively that Grissom was not responsible for the hatch's failure; he remained in the astronaut corps and was a front-runner to command the first moon landing attempt.  NASA John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth, inspects his capsule (Friendship 7) during training.  NASA The first two manned suborbital Mercury flights used the small Redstone missile to carry the spacecraft and astronaut on a parabolic arc; orbital Mercury flights needed the larger Atlas rocket to provide enough delta-v to reach orbit. Pictured here is a Mercury test capsule perched atop an Atlas-D booster.  NASA After Mercury came Gemini. The larger Gemini spacecraft held two astronauts instead of one, seated side-by-side with the commander on the left, just as in an airplane. Here, Jim McDivitt and Ed White simulate a Gemini launch during training.  NASA Gemini VI launches on its Titan II rocket. Gemini VI and VII were launched closely together and were both in orbit at the same time; NASA used the two spacecraft to test and refine its rendezvous procedures. It is the only time two US spacecraft have operated in orbit at the same time (excepting shuttle / ISS operations).  NASA Looking out the cockpit window of Gemini VI at Gemini VII, mere meters away.  NASA During Gemini IV, in June of 1965, Astronaut Ed White became the first American to "spacewalk"—to leave the confines of a spacecraft and operate outside, performing what has come to be known as extravehicular activity, or EVA.  NASA Patricia McDivitt and Patricia White, wives of Jim McDivitt and Ed White, were on hand at the Mission Operations and Control Room during part of the Gemini IV mission. They were able to speak to their husbands over the air-to-ground radio.  NASA NASA Flight Director Gene Kranz sits at his console in the MOCR during Gemini V in August, 1965.  Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott hang out in their Gemini VII spacecraft after splashdown, awaiting recovery.

The giant leap Project Apollo flew toward its goal with sure feet—until the entire program was halted with the deaths of Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee in the Apollo 1 fire. Critically called "a failure of imagination," the fire was technically the result of frayed wiring sparking in an environment of pure, pressurized oxygen—but more correctly, the fire was the result of NASA management and engineers moving too fast to meet what seemed like an impossible end-of-decade deadline. However, the stumble was short-lived. With new rules in place and an improved spacecraft, NASA gathered itself up and, through the combined efforts of more than 400,000 men and women scattered through all corners of the US, won the race. On July 20, 1969, just shy of eight years after President Kennedy's special address to Congress where the moon landing was officially announced to the public, humans set foot on another world for the first time in the history of our species. NASA The crew of Apollo 1: Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. All three were killed on 27 January 1961 by a fire during what was supposed to have been a routine ground test of the Block 1 Apollo command and service module. In order to simulate the vehicle's pressure while in vacuum, the cabin was pressurized with 16.7psia of pure oxygen. A tiny spark from frayed wiring rapidly transformed the capsule's interior into an inferno. The crew were asphyxiated and quickly died; the resulting investigation uncovered mismanagement and issues at many different levels of NASA. Somewhat presciently, Gus Grissom had commented on exactly this kind of situation before his death: "If we die," he wrote, "we want people to accept it. We are in a risky business, and we hope that if anything happens to us, it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life."  NASA The crew of Apollo 1: Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. All three were killed on 27 January 1961 by a fire during what was supposed to have been a routine ground test of the Block 1 Apollo command and service module. In order to simulate the vehicle's pressure while in vacuum, the cabin was pressurized with 16.7psia of pure oxygen. A tiny spark from frayed wiring rapidly transformed the capsule's interior into an inferno. The crew were asphyxiated and quickly died; the resulting investigation uncovered mismanagement and issues at many different levels of NASA. Somewhat presciently, Gus Grissom had commented on exactly this kind of situation before his death: "If we die," he wrote, "we want people to accept it. We are in a risky business, and we hope that if anything happens to us, it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life."  NASA Wernher Von Braun and President Kennedy at Cape Canaveral, discussing one of the early Saturn rockets being built. Von Braun was a former German scientist, rescued (though some might say stolen) from Germany at the end of World War II and put to work on the US' rocketry program. He spearheaded the design effort that resulted in the massive Saturn V rocket.  NASA Standing more than 400 feet tall atop the Crawler Transporter and its mobile launcher, the Saturn V and red Launch Utility Tower are wheeled slowly out of the Vertical Assembly Building (later renamed the Vehicle Assembly Building in the shuttle era) at Cape Kennedy, Florida.  NASA Apollo 11 blast off from the pad at Launch Complex 39A on 16 July, 1969. With Apollo 11, NASA managed to meet Kennedy's challenge to land on the moon at the end of the decade with several months to spare.  NASA Moonwalker Buzz Aldrin in the cabin of Eagle, Apollo 11's lunar module.  NASA In one of the most famous and most reproduced photographs ever taken, Buzz Aldrin stands in the foreground at Mare Tranquillitatis. Visible in his gold-plated visor is Neil Armstrong, who took the photo.  NASA The view out of Neil Armstrong's landing window in Eagle. Flag and footprints are clearly visible. Also of note is the abnormally close horizon; the moon's small diameter plays havoc with our earth-developed ability to estimate distances.  NASA Buzz Aldrin's footprint in the regolith. This is another widely-reproduced iconic photo.  NASA Neil Armstrong, shortly after returning to Eagle's cabin. The Ohio native was just shy of his 38th birthday when he commanded the first lunar landing.  NASA Earthrise, taken from Apollo 11's command module Columbia.  NASA In yet another reminder that nothing about space travel is routine, flight directors huddle in MOCR2 discussing the stricken Apollo 13 mission. While in transit to the moon, one of the spacecraft's oxygen tanks exploded, crippling the command and service module.  NASA The Apollo 13 crew used their lunar module, Aquarius, as a temporary lifeboat during the mission. Aquarius couldn't handle the amount of carbon dioxide exhaled by all three astronauts, and quite famously, couldn't use the command module's extra scrubber cartridges because they were square while the lunar module's were round. NASA engineers very quickly designed a makeshift method to connect the square cartridges to the round receptacles, using only the materials the crew had access to on board. This is famously dramatized in Ron Howard's film, Apollo 13: this fit into the hole for this using nothing but that."  NASA Only after returning to earth and preparing for re-entry did the magnitude of the damage to the Apollo 13 service module become apparent. The exploding oxygen tank had shredded one entire quadrant of the service module; it was feared right up to splashdown that the explosion had also damaged the spacecraft's heat shield. Fortunately, it had not, and the crew returned safely. Apollo 13 has come to be known as "NASA's finest hour," due to the resourcefulness demonstrated by engineers and management in returning the crew alive and unharmed.

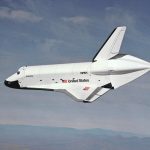

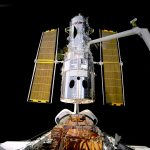

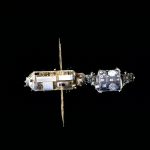

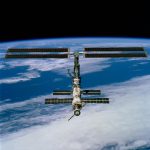

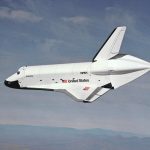

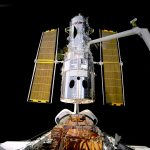

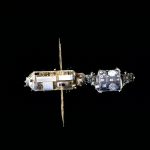

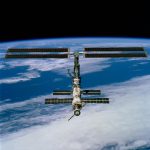

A space pickup truck, and a house to live in Apollo, for all its awesome achievements, was executed with effectively unlimited funds—and because of that, in spite of its success, the program was quickly terminated. It has been famously lamented by more than one astronaut and by several scientists that NASA stopped going to the moon just as they were getting really good at it. Several programs made use of surplus Apollo hardware—the Skylab program launched a space station made up of a Saturn V's S-IVB upper stage into orbit and used Apollo spacecraft to ferry crew to it; the final Apollo flight was the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, where a US and Soviet spacecraft docked in orbit and the crew exchanged symbolic gifts and ate a meal together. But the future, NASA felt, was in reusable spacecraft. All previous US spacecraft had been single-shot affairs, but in order to make access to space truly affordable, NASA envisioned their next craft as fully reusable end-to-end. It would launch like a rocket, ferry people or cargo to space, land like a plane, be refitted, and launch again days later. NASA initially wanted this Space Transport System, or STS, to fly dozens of times in any given month. Space flight would become safe, cheap, and routine. Of course, the Space Shuttle never flew dozens of times per month—or even dozens of times per year. The resulting vehicle was designed with input from lots of government agencies, including the NRO and the Air Force, as NASA hoped to drive down its aggregate launch costs by hauling military payloads to orbit along with civilian ones. In January 1986, the world was reminded that space travel was not routine when the shuttle Challenger was destroyed on launch. As with the Apollo 1 fire, the problem ultimately had its root in NASA's management and culture more than in the technical. Unusually cold temperatures the morning before Challenger's launch caused rubber gaskets in her solid rocket motors to become brittle. The temperatures were far below those in which the gaskets had been designed to operate, but NASA management OK'd the launch anyway. Seven men and women, including a teacher, lost their lives in the accident. The shuttle program continued, and its goals evolved. After struggling through many different design iterations, NASA and several other countries began work on the International Space Station, which would go on to become one of the most expensive construction projects in the history of the world. The ISS relied on the lifting capacity of the Space Shuttle fleet to move its parts into orbit (though a station of similar mass could have been lofted by just five Saturn V rockets rather than the dozens and dozens of shuttle flights necessary). More than twice as many spacewalks than had previously occurred in the entire history of space flight were required to bolt the ISS's modules together. The station slowly grew from a pair of docked modules to a sprawling complex bigger than an American football field. The era of the shuttle drew to a close, but not without a final tragedy. Columbia, the oldest of the orbiter fleet (except for poor mothballed Enterprise) was destroyed on 1 February, 2003. Columbia was lost due to a design decision made early in the shuttle program: a piece of foam sheared off of her external tank and collided with the fragile panels on the leading edge of her left wing, which in turn allowed superheated plasma to infiltrate her structure during re-entry. The shuttle's position next to her tankage instead of on top of it, as all previous spacecraft were placed, contributed more than anything else to the accident. Once again, seven men and women died. I remember attending the memorial service at the Johnson Space Center. It was a hard day. In spite of tragedy, the program marched on. The remaining shuttle fleet completed construction on the International Space Station, which is even now whizzing along above our heads, still alive, doing science. NASA After Apollo, NASA used the leftover hardware for several different stopgap missions. One of the most ambitious was Skylab, which was a space station made out of a Saturn V S-IVB upper stage. More surplus Apollo spacecraft were used to crew and service Skylab. The station was manned from 1973 to 1974, and de-orbited in 1979.  NASA After Apollo, NASA used the leftover hardware for several different stopgap missions. One of the most ambitious was Skylab, which was a space station made out of a Saturn V S-IVB upper stage. More surplus Apollo spacecraft were used to crew and service Skylab. The station was manned from 1973 to 1974, and de-orbited in 1979.  NASA Former Mercury astronaut Deke Slayton never got his chance to fly in the Mercury days—he was grounded because of a recurring atrial fibrillation, and ran NASA's astronaut corps as chief astronaut, where he selected the crews that flew the Apollo missions. The final Apollo flight in 1975 was to be a joint US-USSR rendezvous named the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project; after undergoing a lengthy medical check-out, Slayton somewhat controversially selected himself as one of the crew (though not as the mission's commander). After the longest ever delay between selection and mission assignment, Slayton finally got his gold astronaut wings.  NASA OV-101, the first spacecraft to be named Enterprise, conducts an approach and landing test in 1977. Enterprise—so named as a result of a letter writing campaign conducted by Star Trek fans—flew on her own a total of five times in 1977 and allowed astronauts to practice gliding the space shuttle to a landing. She was also used to perform fit and structural tests for other shuttle stack components, and to check out the fit of shuttle hardware at launch sites.  NASA Columbia takes flight as STS-01, the inaugural lift-off of the space shuttle program. Initially, the space shuttle's external tank was painted white (both for heat resistance and also to match the rest of the vehicle), but after the first two flights NASA dropped the paint in order to save several hundred pounds of weight.  NASA Columbia glides overhead on final approach as her second mission, STS-02, comes to an end.  NASA Photo of Challenger during STS-7, taken by the Space Pallet Satellite after being released from the cargo bay.  NASA Astronaut Bruce McCandless II floats further away from his spacecraft than any other astronaut has before or since. McCandless was testing the Manned Maneuvering Unit, a jet-powered backpack intended to let astronauts move around in EVA untethered. In this famous image, from STS-41B, McCandless is approximately 320 feet (97 meters) away from Challenger  NASA Image of ice on the pad on the morning of 28 January, 1986. The unexpectedly cold weather was outside of the operational parameters of the solid rocket boosters' large rubber gaskets ("O-rings"), but NASA management elected to fly anyway.  NASA In this image taken moments before Challenger's disintegration, burn-through from the failing O-ring is clearly visible. The plume of propellent extended horizontally from the site of the failure, puncturing the external tank. The shuttle stack quickly broke apart; evidence suggests that the crew was likely alive and possibly even conscious during the interminable, horrifying 165 second plunge to the surface of the ocean.  NASA Challenger's remains are permanently interred here in a repurposed missile silo at the Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 31.  NASA No pause lasts forever. NASA put its house in order and got back to flying. Here, Atlantis rockets away from the pad as STS-27. This was the second flight after the hiatus brought about by the Challenger disaster.  NASA The space shuttle does what only the space shuttle can do. Discovery services the Hubble Space Telescope on STS-82, replacing many of the telescope's sensors. Servicing satellites on-orbit was one of the many initial design goals of the shuttle; the enormous cost of shuttle operations eventually made this capability less economical than simply launching new satellites. However, on rare occasions like with the Hubble, the shuttle was exactly the right tool for the job.  NASA The oldest member of the fleet, Columbia, was lost on 1 February 2003. I was working at Boeing at the time and I was one of many who dropped flowers off at this memorial at the main gate outside of the Johnson Space Center. On 4 February, I was also among the hundreds who gathered at JSC to attend the memorial service. At the end, a flight of T-38s screamed barely 200 feet overhead in the Missing Man formation. I will remember the sights and sounds of that moment for the rest of my life.  NASA After Columbia, shuttles began to perform an elaborate pirouette as they approached the International Space Station for docking. The purpose was to present every portion of the shuttle to the ISS crew for visual inspection, to make sure no chunks of foam had nicked any tiles. Here, Discovery serenely keeps station just off of the ISS while she is looked over.  NASA STS-130 was the penultimate flight of Endeavour and also the final night launch of the shuttle program. I was lucky enough to be in attendance at the STS-130 launch, and I got to see Endeavour fling herself skyward with my own eyes. As she pierced the cloud layer, light from her rockets instantly diffused through the clouds and brought a brief false dawn to the Florida coast.  NASA From small beginnings, great things are grown. Here, in December 1998, the US-built Unity module ("Node 1") is docked to the Russian Zarya Functional Cargo Block. It was the first component connection for the International Space Station.  NASA Construction proceeded apace for more than ten years, and the billions of dollars began to multiply. In December 2000, the station had gained many more modules, including the first of four enormous wing-like solar panels.  NASA Building the ISS required a tremendous amount of training; astronauts (and cosmonauts) from assorted countries learned a tremendous amount about construction techniques in microgravity.  NASA Here, two astronauts work on one of the station's Integrated Truss Structure modules. The truss is the ISS's most visually-recognizable component and stretches across the station's transverse axis. It holds the station's solar panels, radiators, and many other structures.  NASA The ISS in 2011, with most of its core component modules in place.

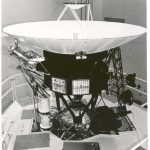

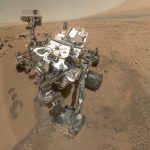

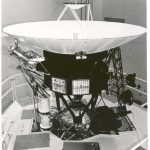

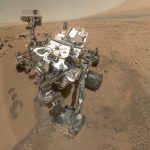

Ever faithful: Far-flung robotic servants For all the glamour of astronauts and their flags and footprints, there is another hugely important aspect of NASA: its robotic probes and spacecraft. If manned space flight stirs the soul, robot space flight has expanded the mind. A comprehensive accounting of the probes and robots dispatched by NASA would fill its own huge long-form article; we can focus on just a few. The two Voyager spacecraft, best-known of NASA's deep space probes, passed through the outer planets and delivered stunning imagery and data. They will be the first man-made objects to leave the solar system. Before Voyager, the twin Pioneer probes charted the outer solar system and beamed back their own images and observations; taken together, Pioneer and Voyager are the most distant objects that have been touched by human hands. And, of course, we must make mention of the wildly successful—and wildly popular—Mars rovers. Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, and now Curiosity—no collection of machines have received as much adulation and praise as those little cars on Mars. Even if humans have for now ceased leaving the confines of our world, we still explore through our surrogates. NASA Pioneer 10 in 1971. The spacecraft was one of the first man-made objects to visit the outer solar system.  NASA Pioneer 10 in 1971. The spacecraft was one of the first man-made objects to visit the outer solar system.  NASA Drawing of the plaque affixed to the Pioneer probes' exteriors. The plaque uses the hyperfine transition of hydrogen to define units of time, which are then used to describe the position of our solar system relative to 14 pulsars (with their frequency described in binary notation derived from the hyperfine transition). Also visible are a nude man and woman, positioned next to a rough representation of the Pioneer spacecraft for scale.  NASA The much larger, much more capable Voyager probes followed Pioneer. Voyager 1 and 2 were constructed to take advantage of a "grand conjunction" of the solar system's outer planets—the planets relative proximity to each other made it possible to fly by many of them in a single visit.  NASA The Voyager probes were equipped with a "Golden Record," inscribed with voices, music, and sounds from Earth. The cover of the record, shown here, featured instructions on how to play the record with its included cartridge, and also how to interpret the video images contained on the disk. The Golden Record contained the same pulsar-based map on how to locate our solar system, but it did not show the same naked man and woman figures; their inclusion on the Pioneer plaques drew public criticism over pornography in space. (Seriously.)  NASA The Voyager spacecraft returned a veritable cornucopia of data on the outer planets, including stunning images of Jupiter and Saturn.  NASA The next visitor to the Jupiter system was the Galileo probe in 1995. The probe was originaly scheduled to be launched on Atlantis in 1986, but the Challenger disaster postponed it for many years. Finally launched in 1989, Galileo spent eight years doing science around Jupiter.  NASA NASA has spent a lot of attention on Mars, our nearest planetary neighbor. The Viking probes were the first American spacecraft to touch down on the red planet; shown here is an image sent back from Viking 2 from its landing spot at Utopia Planitia.  NASA The twin rovers Spirit and Opportunity made big headlines when they reached the Martian surface in 2004. Originally designed for only 90 "sols" (Martian days) of operation, both rovers clobbered their expected design life. Spirit's mission was officially ended on 25 May 2011, while Opportunity continues to soldier bravely on.  NASA This is an image of a rock named "Esperance," taken by Opportunity. Analysis of the rock's mineral content points to the likelihood that it was altered by water at some point in the distant past.  NASA The Mars Science Laboratory Rover, Curiosity, under construction in late 2011 at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab in California. Curiosity is the largest, most sophisticated planetary rover ever constructed.  NASA A "selfie" taken by Curiosity (actually assembled from a mosaic of selfies). The rover captured the public's imagination with its daring, Rube Goldberg-ian skycrane touchdown on Mars.

The next 55 years The future for NASA is complex. I'm a fan of space—in case you haven't figured that out yet—but NASA is an agency undergoing a crisis of leadership. There is no clear mission for NASA's manned space flight directorate, and that lack of mission can be blamed squarely on the Congress and on NASA's administrators. There is no inspiring plan, no consistent messaging, no sensible goal, and, most damning, insufficient funding to accomplish any mission of significance (and a manned asteroid landing, the agency's current vaguely-stated goal, is not a mission of significance). If this set of image galleries seems biased toward the glories of the past, there is reason: NASA is not now what it was. Decades of stagnation and bad leadership across multiple levels of management have cause the agency to take on the aspect of a nursing home-bound pensioner—once lively and spry and able to accomplish literally anything, and now plodding forward while spending an inordinate amount of time recalling past glories. My generation, raised in the 1980s and 90s, has had no moon shot—no triumph of science and imagination. Instead, we've been able to see mankind venture timidly back and forth into low earth orbit, never even leaving its own front yard. It is more than disappointing—it's dispiriting. I expect more from an agency whose mission by its very nature is designed to generate awe. NASA is failing, and it deserves to be saved. Listing image by NASA

via Science - Google News http://news.google.com/news/url?sa=t&fd=R&usg=AFQjCNER6caNTuN3jMP39QjAupiaJwVIXA&url=http://arstechnica.com/science/2013/07/gallery-55-images-for-nasas-55th-anniversary/ |

No comments:

Post a Comment